12.12 Spatial Scans with the STIS CCD

Spatial scanning, which is a supported mode for WFC3 observations (see WFC3 ISR 2012-08: Considerations for using Spatial Scans with WFC3), can also be used with the STIS CCD as an available-but-unsupported mode. For a bright target, this can potentially allow signal-to-noise levels of perhaps as high as a thousand to one to be obtained, even at wavelengths where the STIS CCD is affected by strong IR fringing. This can be especially valuable at wavelengths that are also strongly affected by telluric features in ground-based spectra. Many such regions can be observed with the STIS G750M at wavelengths up to 10140 Å (1.014 μm), with a resolving power close to 10000, allowing weak features such as diffuse interstellar bands to be observed with an accuracy not achievable by any other means. High-S/N ratio time series observations may also be obtained with spatial scans (e.g., for studies of exoplanets and their atmospheres).

Spatial scans are currently not available with STIS MAMA observations.

12.12.1 Why Use Spatial Scans with STIS?

Trailing an external point source in the spatial direction during a first-order STIS CCD spectral observation can spread the target's light over a much larger area of the detector than would be the case for a simple pointed observation. This has several potential advantages:

- Many more photons can be collected before reaching the detector full well saturation limit.

- Spreading the light over a larger fraction of the detector area will better average over flat field variations.

- Trailing along a long slit can result in IR fringing patterns that are significantly closer to the fringing patterns produced by the available contemporaneous tungsten lamp flats, leading to much improved near-IR fringe removal.

- A wider variety of algorithms can potentially be used to detect and remove hot pixels and cosmic rays.

However, spreading the source light over a larger area of the detector can also significantly increase the dark current and read-noise in the extraction region, so the advantages of spatially scanned spectra will be most significant for very bright targets.

12.12.2 Possible STIS Spatial Scan Use Cases

Trailing along a Narrow Slit to Maximize S/N and Fringe Removal

The initial on-orbit applications of this technique were performed by HST programs 14705, 15429, and 15478, as reported by Cordiner et al. (2017, ApJ, 843, L2; 2019, ApJ, 875, L28). Signal-to-noise ratios in excess of 600:1 per resolution element were achieved for G750M spectral observations of moderately reddened stars near 9300 Å, enabling the detection of weak interstellar absorption lines attributed to C60+. In this case, the narrow 52X0.1 aperture was used for both the trailed external observations and the internal lamp flats. As the STIS PSF near that wavelength is relatively wide compared to the slit, the fringing pattern from the lamp and the trailed external target are very similar, which greatly facilitates the fringing correction.

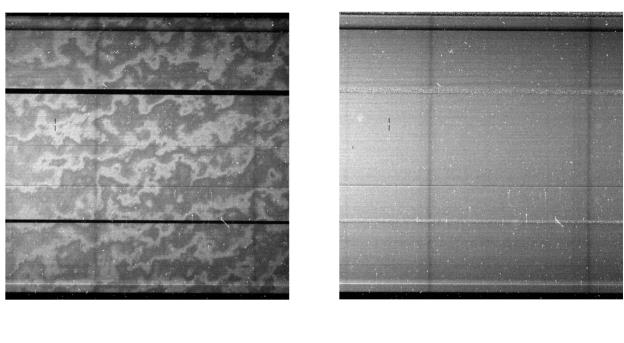

In Figure 12.8, we show an example of one of the trailed spectral observations before and after a simple division by the contemporaneous fringe flat. The very effective removal of the fringing pattern allows detection of much weaker spectral features (vertical dark bands in the image) than would be possible for a simple pointed image.

G750M exposure od9d02vcq of a bright star from program 14705, before (left) and after (right) dividing by a contemporaneous fringe flat image. In these images, wavelength increases to the right, and the star was scanned in the vertical direction along the length of the 52 × 0.1 aperture. This is highly effective at removing the fringing pattern, but does reveal that instability in the trail rate results in noticeable flux variations as a function of the position along the trail direction.Trailing along a Wide Slit to Maximize Photometric Repeatability

While use of a narrow slit does ensure the best fringe removal and is recommended for programs aimed at measuring the absolute equivalent widths of weak features, it does compromise the absolute flux calibration of the observations.

STIS special calibration program 15383 recently obtained scanned G750L observations of the known exoplanet host star 55 Cnc, including scans in both the narrow 52X0.1 and the wider 52X2 apertures. The second visit in the program included a series of repeated 12" long scans along the wider aperture, over the course of two successive orbits, that have yielded encouraging results on the absolute repeatability of flux measurements obtainable with scanned G750L observations. Application of custom procedures for cosmic ray removal, the recently developed python defringe tool, and a de-trending procedure commonly used for analyses of spectral time series observations (e.g., Sing et al. 2011, A&A, 527, A73) yielded an rms scatter in the resulting total fluxes of order 30 ppm. That is comparable to the best precision previously obtained for time series photometry with HST via the more traditional technique of taking saturated spectra at a fixed pointing (STIS ISR 1999-05), which has commonly been used for transiting planet observations with STIS. Detailed analyses of the 15383 data are summarized in the September 2020 STAN. A more detailed discussion, including results from a longer series of scans encompassing a transit of the super-Earth 55 Cnc e obtained under follow-on program 16442, will be given in a paper in preparation.

Variations in the trail rate are also visible during the wide aperture scans, and this will probably hinder any use of trailed STIS observations to model source flux variations during an individual scan; it remains to be determined what limits this may place on the accuracy and repeatability of the integrated flux for individual scanned exposures.

12.12.3 Using STIS Spatial Scans

As STIS spatial scans are an "available-but-unsupported" mode, only a limited amount of tuning has been done to optimize this mode. In brief, to scan along one of the long apertures, one must specify the starting location (in arcsec, relative to the aperture fiducial point; using the POS TARG special requirement), the scan rate (in arcsec s–1; see below), the scan orientation (nominally 90 degrees), the scan direction, and the total exposure time. The scan length is then given by the product of the scan rate and the exposure time; the Y coordinate of the starting location should be specified to position the scan as desired on the detector. Currently, "forward" scans place the spectra at close to the intended position, but there is apparently a timing error in the implementation of "reverse" scans that result in them being offset on the detector to higher than intended Y locations, with larger offsets at higher scan rates. As a result, we currently recommend that STIS observers use only "forward" scans and avoid both the "reverse" and "round-trip" options. Because different apertures can map to slightly different positions on the detector, when scanning up the 52X2 and doing fringe flats with the 52X0.1, the procedure should be to first peak up in the 52X0.1, and then add an X component to the POS TARG for the 52X2 scan to correct for the –0.049241721" difference in SIAF X locations between the two apertures.

Visit 01 of program 15383 took scanned imaging observations to check the alignment of the default scan angle with the science apertures. This visit suggested a small correction to the default scan angle of ~+0.065 degrees, but the repeatability of this correction has yet to be verified.

For more information about proposing for spatial scanning using STIS, please see Section 6.3.1 in the Phase II Proposal Instructions.

Using the ETC to Estimate Scan Parameters

Currently the STIS ETC does not support calculations for scanned observations. However, to achieve the expected flat-fielding improvements, it is essential to avoid saturating the detector.

To estimate the expected peak flux levels, we recommend beginning with a spectroscopic ETC calculation of a pointed observation with CR-SPLIT=1 for the requested total exposure time of an individual scan with all other parameters set as they will be for the actual observation. Then go to the "Table of Source and Noise Counts per Pixel" on the ETC results page. In this table, "pixel" refers to a pixel in the extracted 1D spectrum which is actually a sum in the original 2D image over 1 pixel in the dispersion direction and the extraction height (7 pixels by default for the STIS CCD), in the spatial direction, while the "counts" given in this table are always in units of electrons, regardless of the gain setting. The source counts/per pixel in this table have been scaled by the wavelength dependent fraction, E, of the total source flux at that wavelength that is expected to fall within the extraction height, and this excluded light in the wings of the PSF will contribute to the counts accumulated during the scan. For the G750L grating the encircled energy fraction in the 7 pixel region varies from ~0.8 at 6000 Å, to about 0.6 at 10000 Å. If S is the "Source Per Pixel" in the ETC table and L is the length of the scan in pixels (the scan length in arcseconds divided by 0.0508"/pixel), then the approximate local source count rate in electrons per second per pixel in the scanned 2D image will simply be S/E/L; this is the number that should be compared to the saturation limits.

Because the spectrum will be spread over a larger region of the detector than was assumed in the ETC, for obtaining a good S/N estimate for fainter targets it will also be necessary to scale the dark current, sky background, and the read-noise squared from the values calculated for the default extraction height to the actual area to be used in the final extraction. If these are significant compared to the source count rate, then the final signal-to-noise should be manually computed using the equations in Section 6.4. If the read-noise and dark current are negligible compared to the Poisson noise of the source counts, then the S/N estimate in the original ETC calculation is probably as good an approximation as any available.

As a concrete example, the following describes the calculation for one of the series of 218.1 s exposures done in the 2nd and 3rd orbits of visit 11 of program 15383. The scan rate there was set to 0.055 arcsec/sec, which yielded a scan length of 12 arcseconds or about 236 pixels. An ETC calculation for a pointed exposure with the same parameters is given by http://etc.stsci.edu/etc/results/STIS.sp.1044073/. At 5828.9 Å, the tabular data page for this ETC calculation gives about 1.48e7 electrons as the "source per pixel". For the scanned observation, we would then predict about 1.48e7/0.8/(12/0.0508) = 78317 e–, or for GAIN=4 about 19500 DN in each pixel of the FLT image. The contribution from the dark current is negligible, and examination of the FLT file for exposure ODQF11UOQ shows that the mean count rate in the column corresponding to this wavelength is indeed very close to 19500 DN, although the actual value fluctuates from row-to-row by up to 10% due to variations in the scanning rate during the observation. To account for scan rate variations, fringing effects, and other approximations in the ETC calculations, we recommend keeping the planned peak source counts for GAIN=4 STIS CCD observations below about 100,000 e– in each pixel of the 2D image.

Setting Fringe-Flat Exposures for Spatial Scans

The supported TARGET=CCDFLAT exposures available in APT to provide tungsten lamp IR fringe flats have relatively modest default exposure times, intended to support the S/N requirements of pointed observations. Using this option for the fringe flats prohibits exposure times greater than the default values from being used.

Since scanned observations can collect many more photons per resolution element than is possible in pointed observations, it may sometimes be useful to take deeper tungsten lamp images than are supported with TARGET=CCDFLAT. This can be done when available modes are enabled by setting TARGET=NONE, and adding the special requirement LAMP=TUNGSTEN. It is then the responsibility of the user, however, to set the exposure and instrument parameters, as the default settings differ from those used with TARGET=CCDFLAT. Note also that APT does not recognize TARGET=NONE exposures as CCDFLAT exposures and will complain of missing fringe flats, whether or not the parameters are set correctly. This warning will be spurious, however, when the appropriate TARGET=NONE, LAMP=TUNGSTEN exposures are actually there. It is important to note that setting TARGET=NONE is an available-but-unsupported mode and will require scientific justification and approval.

The overhead on each individual tungsten lamp exposure can be significant, and it will often be significantly more efficient to take a few deep lamp exposures rather than a number of shorter ones using the CCDFLAT default times. Observers must be careful to not saturate the longer fringe flat exposures, however.

The fringing correction is very sensitive to the exact distribution of wavelengths falling on each pixel of the detector, and shifts in instrument alignment can cause noticeable changes over the course of a single visibility period. For this reason, the science and fringe-flat exposures should be accurately registered (e.g., if taken through different apertures), and it may sometimes be useful to intermingle fringe-flat lamp exposures with the external science exposures, even if this reduces the time available to observe the external target.

-

STIS Instrument Handbook

- • Acknowledgments

- Chapter 1: Introduction

-

Chapter 2: Special Considerations for Cycle 33

- • 2.1 Impacts of Reduced Gyro Mode on Planning Observations

- • 2.2 STIS Performance Changes Pre- and Post-SM4

- • 2.3 New Capabilities for Cycle 33

- • 2.4 Use of Available-but-Unsupported Capabilities

- • 2.5 Choosing Between COS and STIS

- • 2.6 Scheduling Efficiency and Visit Orbit Limits

- • 2.7 MAMA Scheduling Policies

- • 2.8 Prime and Parallel Observing: MAMA Bright-Object Constraints

- • 2.9 STIS Snapshot Program Policies

- Chapter 3: STIS Capabilities, Design, Operations, and Observations

- Chapter 4: Spectroscopy

- Chapter 5: Imaging

- Chapter 6: Exposure Time Calculations

- Chapter 7: Feasibility and Detector Performance

-

Chapter 8: Target Acquisition

- • 8.1 Introduction

- • 8.2 STIS Onboard CCD Target Acquisitions - ACQ

- • 8.3 Onboard Target Acquisition Peakups - ACQ PEAK

- • 8.4 Determining Coordinates in the International Celestial Reference System (ICRS) Reference Frame

- • 8.5 Acquisition Examples

- • 8.6 STIS Post-Observation Target Acquisition Analysis

- Chapter 9: Overheads and Orbit-Time Determination

- Chapter 10: Summary and Checklist

- Chapter 11: Data Taking

-

Chapter 12: Special Uses of STIS

- • 12.1 Slitless First-Order Spectroscopy

- • 12.2 Long-Slit Echelle Spectroscopy

- • 12.3 Time-Resolved Observations

- • 12.4 Observing Too-Bright Objects with STIS

- • 12.5 High Signal-to-Noise Ratio Observations

- • 12.6 Improving the Sampling of the Line Spread Function

- • 12.7 Considerations for Observing Planetary Targets

- • 12.8 Special Considerations for Extended Targets

- • 12.9 Parallel Observing with STIS

- • 12.10 Coronagraphic Spectroscopy

- • 12.11 Coronagraphic Imaging - 50CORON

- • 12.12 Spatial Scans with the STIS CCD

-

Chapter 13: Spectroscopic Reference Material

- • 13.1 Introduction

- • 13.2 Using the Information in this Chapter

-

13.3 Gratings

- • First-Order Grating G750L

- • First-Order Grating G750M

- • First-Order Grating G430L

- • First-Order Grating G430M

- • First-Order Grating G230LB

- • Comparison of G230LB and G230L

- • First-Order Grating G230MB

- • Comparison of G230MB and G230M

- • First-Order Grating G230L

- • First-Order Grating G230M

- • First-Order Grating G140L

- • First-Order Grating G140M

- • Echelle Grating E230M

- • Echelle Grating E230H

- • Echelle Grating E140M

- • Echelle Grating E140H

- • PRISM

- • PRISM Wavelength Relationship

-

13.4 Apertures

- • 52X0.05 Aperture

- • 52X0.05E1 and 52X0.05D1 Pseudo-Apertures

- • 52X0.1 Aperture

- • 52X0.1E1 and 52X0.1D1 Pseudo-Apertures

- • 52X0.2 Aperture

- • 52X0.2E1, 52X0.2E2, and 52X0.2D1 Pseudo-Apertures

- • 52X0.5 Aperture

- • 52X0.5E1, 52X0.5E2, and 52X0.5D1 Pseudo-Apertures

- • 52X2 Aperture

- • 52X2E1, 52X2E2, and 52X2D1 Pseudo-Apertures

- • 52X0.2F1 Aperture

- • 0.2X0.06 Aperture

- • 0.2X0.2 Aperture

- • 0.2X0.09 Aperture

- • 6X0.2 Aperture

- • 0.1X0.03 Aperture

- • FP-SPLIT Slits 0.2X0.06FP(A-E) Apertures

- • FP-SPLIT Slits 0.2X0.2FP(A-E) Apertures

- • 31X0.05ND(A-C) Apertures

- • 0.2X0.05ND Aperture

- • 0.3X0.05ND Aperture

- • F25NDQ Aperture

- 13.5 Spatial Profiles

- 13.6 Line Spread Functions

- • 13.7 Spectral Purity, Order Confusion, and Peculiarities

- • 13.8 MAMA Spectroscopic Bright Object Limits

-

Chapter 14: Imaging Reference Material

- • 14.1 Introduction

- • 14.2 Using the Information in this Chapter

- 14.3 CCD

- 14.4 NUV-MAMA

-

14.5 FUV-MAMA

- • 25MAMA - FUV-MAMA, Clear

- • 25MAMAD1 - FUV-MAMA Pseudo-Aperture

- • F25ND3 - FUV-MAMA

- • F25ND5 - FUV-MAMA

- • F25NDQ - FUV-MAMA

- • F25QTZ - FUV-MAMA, Longpass

- • F25QTZD1 - FUV-MAMA, Longpass Pseudo-Aperture

- • F25SRF2 - FUV-MAMA, Longpass

- • F25SRF2D1 - FUV-MAMA, Longpass Pseudo-Aperture

- • F25LYA - FUV-MAMA, Lyman-alpha

- • 14.6 Image Mode Geometric Distortion

- • 14.7 Spatial Dependence of the STIS PSF

- • 14.8 MAMA Imaging Bright Object Limits

- Chapter 15: Overview of Pipeline Calibration

- Chapter 16: Accuracies

-

Chapter 17: Calibration Status and Plans

- • 17.1 Introduction

- • 17.2 Ground Testing and Calibration

- • 17.3 STIS Installation and Verification (SMOV2)

- • 17.4 Cycle 7 Calibration

- • 17.5 Cycle 8 Calibration

- • 17.6 Cycle 9 Calibration

- • 17.7 Cycle 10 Calibration

- • 17.8 Cycle 11 Calibration

- • 17.9 Cycle 12 Calibration

- • 17.10 SM4 and SMOV4 Calibration

- • 17.11 Cycle 17 Calibration Plan

- • 17.12 Cycle 18 Calibration Plan

- • 17.13 Cycle 19 Calibration Plan

- • 17.14 Cycle 20 Calibration Plan

- • 17.15 Cycle 21 Calibration Plan

- • 17.16 Cycle 22 Calibration Plan

- • 17.17 Cycle 23 Calibration Plan

- • 17.18 Cycle 24 Calibration Plan

- • 17.19 Cycle 25 Calibration Plan

- • 17.20 Cycle 26 Calibration Plan

- • 17.21 Cycle 27 Calibration Plan

- • 17.22 Cycle 28 Calibration Plan

- • 17.23 Cycle 29 Calibration Plan

- • 17.24 Cycle 30 Calibration Plan

- • 17.25 Cycle 31 Calibration Plan

- • 17.26 Cycle 32 Calibration Plan

- Appendix A: Available-But-Unsupported Spectroscopic Capabilities

- • Glossary