7.6 IR Optical Performance

Following WFC3's alignment to the OTA (WFC3 ISR 2009-46), a series of observations through a variety of filters were obtained to demonstrate the instrument's optical performance. The WFC3 IR channel meets or exceeds all image quality expectations. The following subsections summarize the measured flight optical performance for the IR channel, as described by its point-spread function (PSF), i.e., the spatial distribution of the flux in an image of a point source. The results shown are produced using an optical model which has been adjusted and correlated to the PSFs measured on-orbit and represent mean values averaged over the field (WFC3 ISR 2009-37). This PSF model includes the pupil geometry, including the cold stop, residual aberration, the mid-frequency wavefront error of the OTA, the effect of the detector inter-pixel capacitive cross-talk, and first-order geometric distortion.

7.6.1 PSF Width and Sharpness

The IR channel PSFs are well approximated by Gaussian profiles (before pixelation). As was discussed in more detail for the UVIS channel in Section 6.6.1, the PSFs can usefully be characterized by their FWHM or their sharpness, effectively the reciprocal of the number of pixels occupied by a point source (as defined in Section 6.6.1). Table 7.5 lists the FWHM of the model PSF core (before pixelation) in units of pixel and arcsec and the sharpness parameter for 10 wavelengths. The sharpness range shown for each wavelength indicates the values for the PSF centered on the pixel corners and center. The monotonic increase in FWHM and decrease in sharpness with wavelength is due to diffraction.

Table 7.5: WFC3/IR PSF FWHM (before pixelation, in units of pixels and arcseconds), and sharpness, vs. wavelength. (Note that attempts to measure the FWHM by fitting functions to the pixelated PSF will generally yield larger values.)

Wavelength | FWHM | FWHM | Sharpness |

800 | 0.971 | 0.124 | 0.127–0.197 |

900 | 0.986 | 0.126 | 0.118–0.182 |

1000 | 1.001 | 0.128 | 0.109–0.169 |

1100 | 1.019 | 0.130 | 0.100–0.156 |

1200 | 1.040 | 0.133 | 0.093–0.144 |

1300 | 1.067 | 0.137 | 0.087–0.132 |

1400 | 1.100 | 0.141 | 0.083–0.121 |

1500 | 1.136 | 0.145 | 0.080–0.112 |

1600 | 1.176 | 0.151 | 0.077–0.102 |

1700 | 1.219 | 0.156 | 0.074–0.093 |

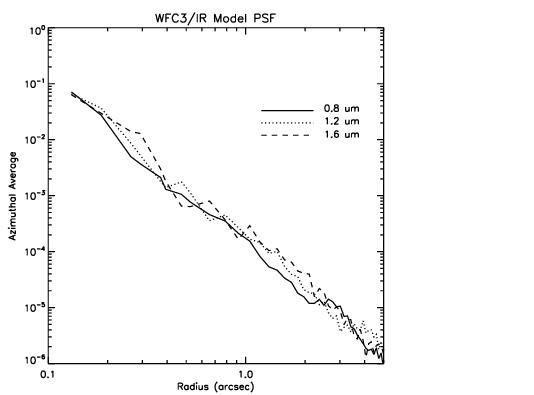

Figure 7.5 plots the azimuthally-averaged model OTA+WFC3 PSF at three different IR wavelengths., indicating the fractional PSF flux per pixel at radii from 1 pixel to 5 arcsec.

7.6.2 Encircled Energy

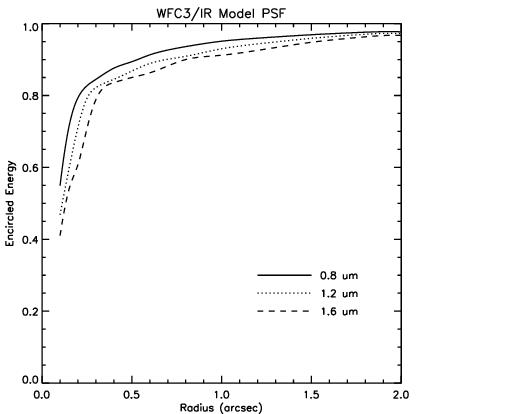

As described in more detail in Section 6.6.2 for the UVIS channel, encircled energy, the fraction of light contained in a circular aperture is one useful way of characterizing well-behaved profiles. Encircled energy profiles for the IR channel model PSF at three representative wavelengths are plotted in Figure 7.6. Empirical encircled energy values for 11 select aperture radii are presented in Table 7.6 (see WFC3 ISR 2009-37 for more details). The WFC3 IR Encircled Energy webpage provides the encircled energy curves for 19 total aperture radii as a downloadable file.

| Filter | Wavelength (Å) | Aperture (arcsec) | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.13 | 0.26 | 0.39 | 0.52 | 0.65 | 0.78 | 0.91 | 1.0 | 1.3 | 2.0 | 6.0 | ||

| F098M | 9865 | 0.596 | 0.818 | 0.857 | 0.887 | 0.905 | 0.922 | 0.934 | 0.943 | 0.956 | 0.974 | 1 |

| F105W | 10551 | 0.577 | 0.811 | 0.852 | 0.882 | 0.901 | 0.917 | 0.929 | 0.939 | 0.953 | 0.973 | 1 |

| F110W | 11534 | 0.553 | 0.797 | 0.845 | 0.873 | 0.895 | 0.909 | 0.922 | 0.933 | 0.948 | 0.97 | 1 |

| F125W | 12486 | 0.535 | 0.789 | 0.841 | 0.867 | 0.89 | 0.904 | 0.918 | 0.929 | 0.945 | 0.969 | 1 |

| F126N | 12585 | 0.534 | 0.789 | 0.84 | 0.867 | 0.89 | 0.904 | 0.917 | 0.929 | 0.944 | 0.969 | 1 |

| F127M | 12740 | 0.531 | 0.787 | 0.84 | 0.865 | 0.89 | 0.903 | 0.916 | 0.929 | 0.944 | 0.968 | 1 |

| F128N | 12832 | 0.529 | 0.786 | 0.839 | 0.865 | 0.889 | 0.902 | 0.916 | 0.928 | 0.943 | 0.968 | 1 |

| F130N | 13006 | 0.526 | 0.784 | 0.838 | 0.863 | 0.888 | 0.901 | 0.915 | 0.927 | 0.942 | 0.968 | 1 |

| F132N | 13188 | 0.523 | 0.78 | 0.838 | 0.862 | 0.887 | 0.9 | 0.914 | 0.926 | 0.942 | 0.967 | 1 |

| F139M | 13838 | 0.513 | 0.769 | 0.836 | 0.858 | 0.882 | 0.898 | 0.912 | 0.923 | 0.939 | 0.966 | 1 |

| F140W | 13923 | 0.512 | 0.764 | 0.837 | 0.86 | 0.882 | 0.9 | 0.912 | 0.923 | 0.94 | 0.967 | 1 |

| F153M | 15322 | 0.496 | 0.74 | 0.835 | 0.856 | 0.876 | 0.899 | 0.909 | 0.918 | 0.937 | 0.967 | 1 |

| F160W | 15369 | 0.494 | 0.736 | 0.833 | 0.855 | 0.875 | 0.897 | 0.908 | 0.918 | 0.935 | 0.966 | 1 |

| F164N | 16404 | 0.483 | 0.713 | 0.829 | 0.852 | 0.87 | 0.894 | 0.905 | 0.914 | 0.932 | 0.963 | 1 |

| F167N | 16642 | 0.48 | 0.706 | 0.828 | 0.851 | 0.869 | 0.893 | 0.904 | 0.913 | 0.931 | 0.962 | 1 |

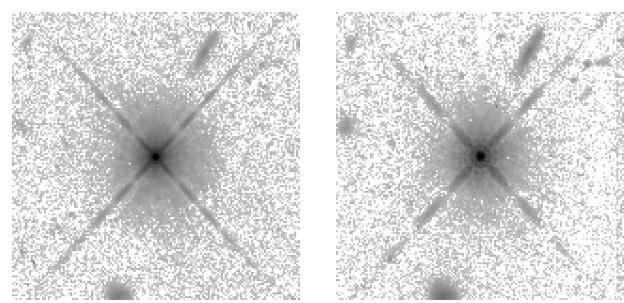

During initial on-orbit tests in SMOV, high-dynamic-range isolated star images were obtained through several filters (WFC3 ISR 2009-37). These are shown with a logarithmic stretch in Figure 7.7. The images appear slightly elongated vertically, due to the 24 degree tilt of the detector to the chief ray and the fact that a distortion correction has not been applied. Although the target was chosen to be isolated, a number of field galaxies appear in both the F098M and the F160W filter images; these are also seen in long wavelength UVIS channel images of the same target (Figure 6.13). Some detector artifacts, including cold and warm pixels and imperfectly removed cosmic ray hits are evident.

7.6.3 Other PSF Behavior and Characteristics

Temporal Dependence of the PSF: HST Breathing

All HST observations are affected to some extent by short-term focus variations (“breathing”), which arise from the changing thermal environment of HST (See Section 6.6.3). For the IR channel, breathing is expected to produce variations of ~0.3% and less than 0.1% in the FWHM of the PSF of WFC3/IR at 700 nm and at wavelengths longer than 1100 nm, respectively, on typical time scales of one orbit.

Intra-Pixel Response

The response of a pixel of an IR detector to light from an unresolved source varies with the positioning of the source within the pixel due to low sensitivity at the pixel's edges and dead zones between pixels. For the WFC3/IR flight detector, no measurable intra-pixel sensitivity variation was found during ground testing (WFC3 ISR 2008-19) or in-flight testing (WFC3 ISR 2011-19). For NICMOS, the intra-pixel sensitivity was found to be an important effect: it varied by as much as 40% (peak to valley). The WFC3 small pixel size (18 µm vs. NICMOS's 40 µm) and the much higher WFC3/IR detector temperature compared to NICMOS are probably responsible for this improvement.

Inter-Pixel Capacitance

The small pixel size, relative to that in NICMOS, increases the relevance of capacitive coupling between nearby pixels (Brown et. al., 2006, PASP, 118, 1443; Moore et. al., 2006, Opt. Eng., 076402). It affects the gain measurements and the PSF. The easiest method of estimating the inter-pixel capacitance is to measure the ratio of DNs in pixels adjacent to a “hot” (high-dark-current) pixel to the DNs in the hot pixel. In the WFC3 IR detector, on the order of 5% of electrons may leak to the adjacent pixels. WFC3 ISR 2008-26 describes a method for correcting inter-pixel capacitance using Fourier deconvolution, and demonstrates its effectiveness on WFC3/IR ground-testing data. WFC3 ISR 2011-10 provides an improved deconvolution kernel with distinct values for each of the 8 pixels surrounding the central pixel.

7.6.4 Super-sampled PSF Models

The concept of empirical net (“effective”) models of PSFs is introduced in Section 6.6.4. The WFC3/IR PSF has recently been modeled in WFC3 ISR 2016-12 for five commonly used filters (F105W, F110W, F125W, F140W, and F160W); these models are available to download on the WFC3 PSF webpage.

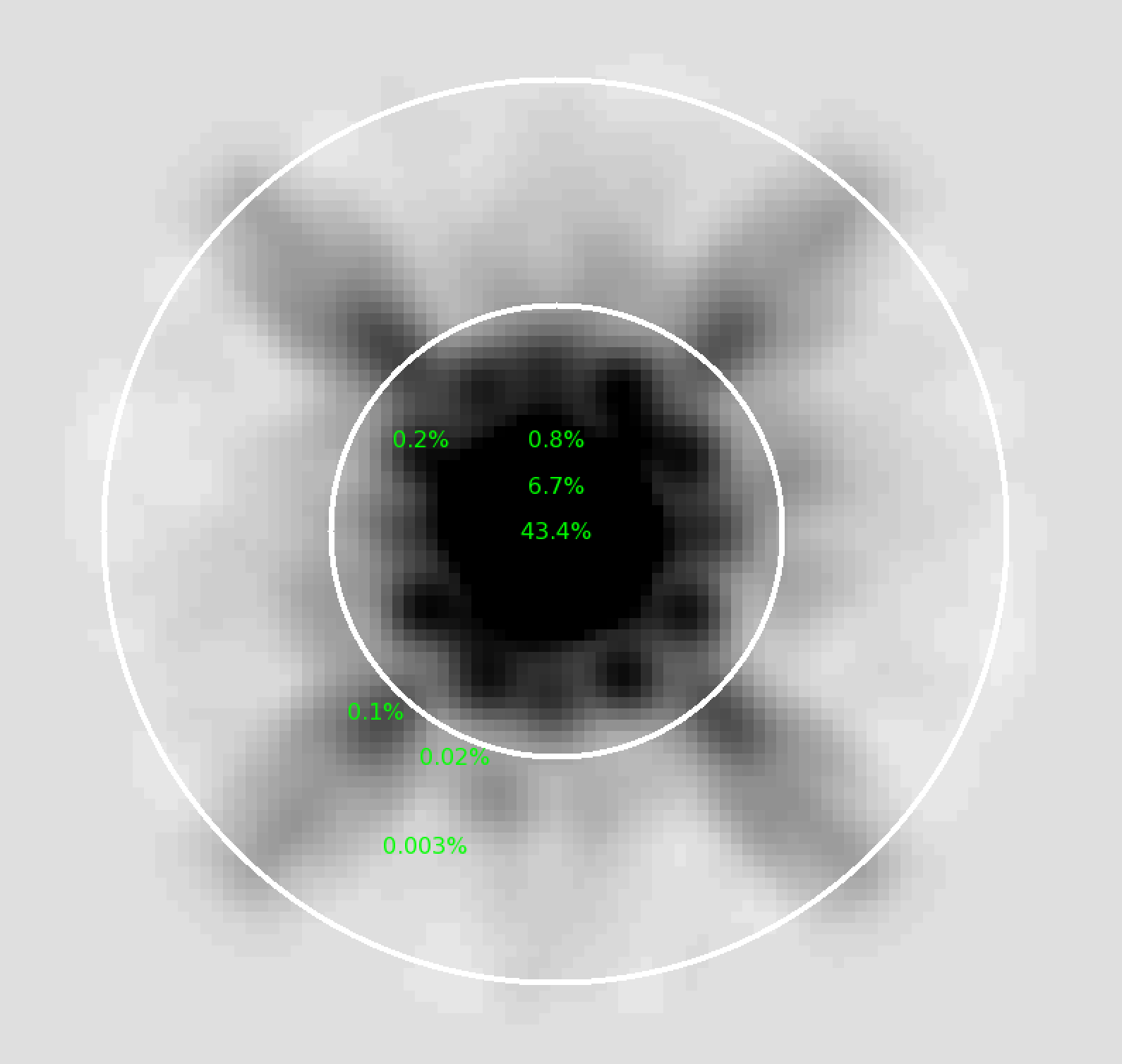

Figure 7.8 shows a log image of the F105W PSF in super-sampled (4x) pixels. The WFC3/IR PSF is extremely under-sampled by the detector pixels: over 40 percent of a star's flux will land in its central pixel if the star is centered on that pixel. Only 4 percent will fall in the directly adjacent pixels. Even with this extreme under-sampling, the 4x super-sampled grid-base model is easily able to represent the PSF.

hst1pass, and WFC3 ISR 2022-05 describes how it can be downloaded and run.In an effort to supplement these super-sampled model PSFs, the WFC3 team recently has built a searchable database of over 5 million WFC3/IR extracted star images (PSFs) from 2009 to 2023 (see WFC3 ISR 2021-12 and the WFC3 PSF Search webpage for more details). These images of PSFs can then be employed to generate PSFs that for users' observations and other science needs.

-

WFC3 Instrument Handbook

- • Acknowledgments

- Chapter 1: Introduction to WFC3

- Chapter 2: WFC3 Instrument Description

- Chapter 3: Choosing the Optimum HST Instrument

- Chapter 4: Designing a Phase I WFC3 Proposal

- Chapter 5: WFC3 Detector Characteristics and Performance

-

Chapter 6: UVIS Imaging with WFC3

- • 6.1 WFC3 UVIS Imaging

- • 6.2 Specifying a UVIS Observation

- • 6.3 UVIS Channel Characteristics

- • 6.4 UVIS Field Geometry

- • 6.5 UVIS Spectral Elements

- • 6.6 UVIS Optical Performance

- • 6.7 UVIS Exposure and Readout

- • 6.8 UVIS Sensitivity

- • 6.9 Charge Transfer Efficiency

- • 6.10 Other Considerations for UVIS Imaging

- • 6.11 UVIS Observing Strategies

- Chapter 7: IR Imaging with WFC3

- Chapter 8: Slitless Spectroscopy with WFC3

-

Chapter 9: WFC3 Exposure-Time Calculation

- • 9.1 Overview

- • 9.2 The WFC3 Exposure Time Calculator - ETC

- • 9.3 Calculating Sensitivities from Tabulated Data

- • 9.4 Count Rates: Imaging

- • 9.5 Count Rates: Slitless Spectroscopy

- • 9.6 Estimating Exposure Times

- • 9.7 Sky Background

- • 9.8 Interstellar Extinction

- • 9.9 Exposure-Time Calculation Examples

- Chapter 10: Overheads and Orbit Time Determinations

-

Appendix A: WFC3 Filter Throughputs

- • A.1 Introduction

-

A.2 Throughputs and Signal-to-Noise Ratio Data

- • UVIS F200LP

- • UVIS F218W

- • UVIS F225W

- • UVIS F275W

- • UVIS F280N

- • UVIS F300X

- • UVIS F336W

- • UVIS F343N

- • UVIS F350LP

- • UVIS F373N

- • UVIS F390M

- • UVIS F390W

- • UVIS F395N

- • UVIS F410M

- • UVIS F438W

- • UVIS F467M

- • UVIS F469N

- • UVIS F475W

- • UVIS F475X

- • UVIS F487N

- • UVIS F502N

- • UVIS F547M

- • UVIS F555W

- • UVIS F600LP

- • UVIS F606W

- • UVIS F621M

- • UVIS F625W

- • UVIS F631N

- • UVIS F645N

- • UVIS F656N

- • UVIS F657N

- • UVIS F658N

- • UVIS F665N

- • UVIS F673N

- • UVIS F680N

- • UVIS F689M

- • UVIS F763M

- • UVIS F775W

- • UVIS F814W

- • UVIS F845M

- • UVIS F850LP

- • UVIS F953N

- • UVIS FQ232N

- • UVIS FQ243N

- • UVIS FQ378N

- • UVIS FQ387N

- • UVIS FQ422M

- • UVIS FQ436N

- • UVIS FQ437N

- • UVIS FQ492N

- • UVIS FQ508N

- • UVIS FQ575N

- • UVIS FQ619N

- • UVIS FQ634N

- • UVIS FQ672N

- • UVIS FQ674N

- • UVIS FQ727N

- • UVIS FQ750N

- • UVIS FQ889N

- • UVIS FQ906N

- • UVIS FQ924N

- • UVIS FQ937N

- • IR F098M

- • IR F105W

- • IR F110W

- • IR F125W

- • IR F126N

- • IR F127M

- • IR F128N

- • IR F130N

- • IR F132N

- • IR F139M

- • IR F140W

- • IR F153M

- • IR F160W

- • IR F164N

- • IR F167N

- Appendix B: Geometric Distortion

- Appendix C: Dithering and Mosaicking

- Appendix D: Bright-Object Constraints and Image Persistence

-

Appendix E: Reduction and Calibration of WFC3 Data

- • E.1 Overview

- • E.2 The STScI Reduction and Calibration Pipeline

- • E.3 The SMOV Calibration Plan

- • E.4 The Cycle 17 Calibration Plan

- • E.5 The Cycle 18 Calibration Plan

- • E.6 The Cycle 19 Calibration Plan

- • E.7 The Cycle 20 Calibration Plan

- • E.8 The Cycle 21 Calibration Plan

- • E.9 The Cycle 22 Calibration Plan

- • E.10 The Cycle 23 Calibration Plan

- • E.11 The Cycle 24 Calibration Plan

- • E.12 The Cycle 25 Calibration Plan

- • E.13 The Cycle 26 Calibration Plan

- • E.14 The Cycle 27 Calibration Plan

- • E.15 The Cycle 28 Calibration Plan

- • E.16 The Cycle 29 Calibration Plan

- • E.17 The Cycle 30 Calibration Plan

- • E.18 The Cycle 31 Calibration Plan

- • E.19 The Cycle 32 Calibration Plan

- • Glossary